Look closely at a military uniform or a court dress and you will likely see row after row of the tiniest coiled metal wires, some with a dull shine, others that reflect light like a diamond. Each coil of wire will have been meticulously placed by hand with a single needle and thread. They are secured and couched into place over hundreds of hours to build complex patterns and flora. But what are they and why are they so special?

Even today, in the age of AI, skyscrapers and satellites, heavily embroidered ceremonial uniforms still impress and intimidate the casual viewer. To most, the precision tailoring, the ornate detailing and the rich textures remain a perplexing mystery.

A vast amount of skilled craftsmanship goes into ensuring these enigmatic garments stir feelings of awe. For the makers, designers and wider culture that conceived of such uniforms, that was the purpose.

Refined embroidery was, and remains, central to achieving that goal.

Considering the specifics of these uniforms, let us look at the surface decorations that create such a rich texture. Goldwork embroidery is the complex surface decoration frequently applied to uniforms, ceremonial apparel and (more recently) high fashion. This ancient embroidery technique can be traced back to antiquity in Egypt, Greece and Rome as well as China during the Tang Dynasty (618-907 AD).

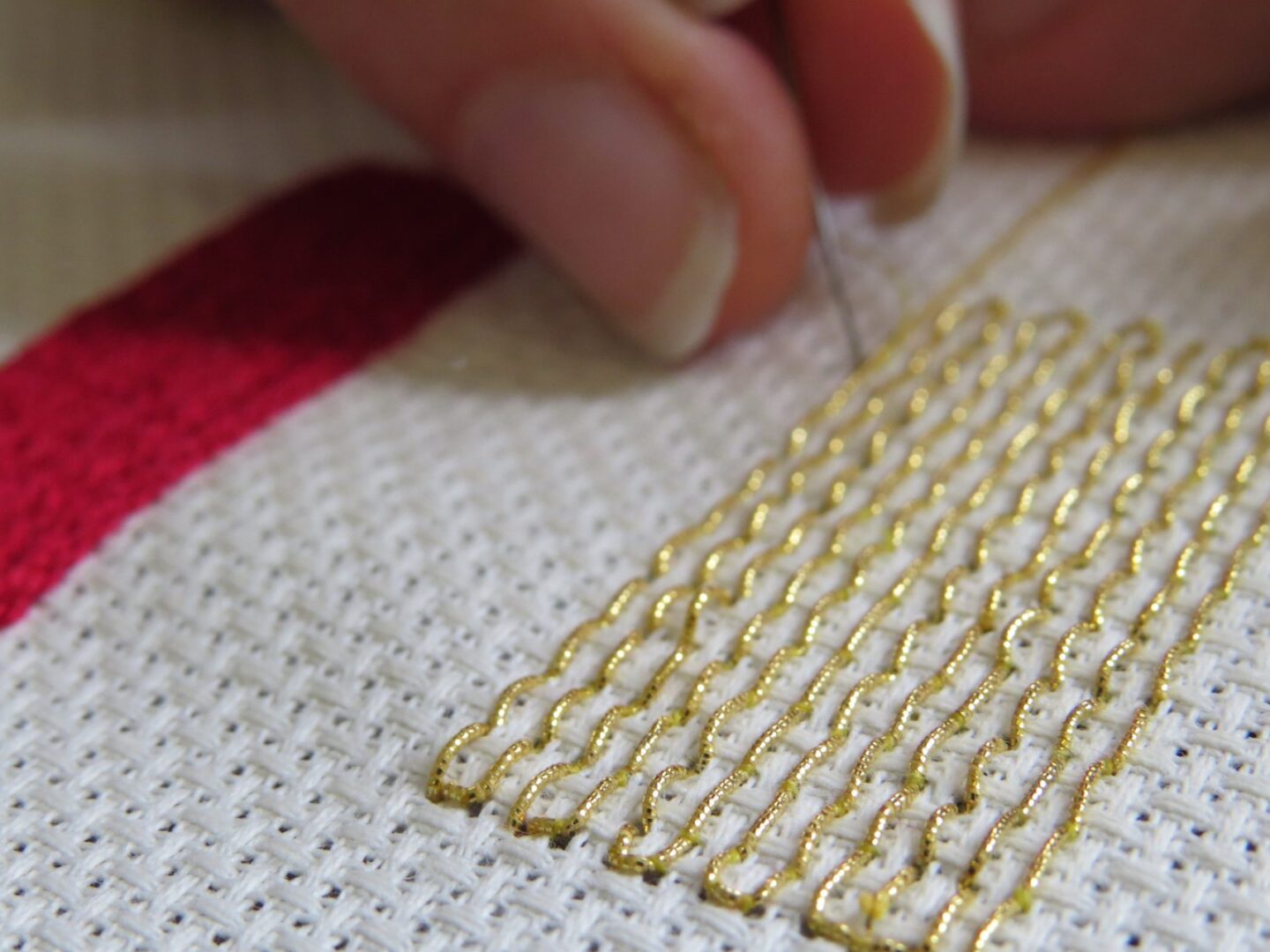

For gold cloth, gold is combined with other metals and then spun into fine threads which can be woven into cloth. In the case of embroidery, the same gold might be spun into fine wires and applied as decoration directly to the surface of a garment. This latter use has evolved over the centuries with more complex and impactful techniques being developed. Collectively, the application of these fine metal wires, regardless of colour, is called goldwork.

Modern day goldwork is practised by only a handful of specialist embroidery houses around the world. London’s Hand & Lock, an esteemed embroidery house dating from 1767, are widely recognised as masters of goldwork and one of the few places in Britain trusted to restore and repair goldwork. Teachers of the fine art, they seek to promote understanding and appreciation for goldwork and inspire future generations to preserve and embrace the practice.

But before we look to the future, we must look to the past to better understand the origins of this metallic aesthetic.

In mediaeval Europe, goldwork embroidery became increasingly popular with the church, where it was used to adorn religious vestments and altar cloths.

Rather than ‘Goldwork’, this exact strand of embroidery was known as ‘Opus Anglicanum’ or ‘English Work’. Practised in small communities across England, it became popular throughout Europe in the 13th and 14th centuries. The principal materials used to create the intricate imagery on the religious vestments were gold and silver metal threads. These fine metal threads were made by taking a thin strip of metal and winding it around a silk thread.

Often referred to as ‘passing’, this material was then laid flat on the base fabric and secured in place with an embroidery technique known as ‘underside couching’.

With this technique, a single silk thread would come up through the base material, and loop around the passing before returning through the same hole in the fabric. The loop would then be pulled tight and then drawn through to the underside bringing the passing with it, making a subtle ‘pop’ sound. This technique was prized for creating tiny hinges along the rows of gold passing, reducing stiffness and encouraging the natural movement and drapery of the material.

The name ‘Opus Anglicanum’ was used to describe the very best ecclesiastical goldwork that was being made anywhere in the world and many of the pieces were so important they still remain today.

The ubiquity of English Medieval embroidery established a new language of power, status and wealth across Europe and the world. Gradually this meaning would shift from the religious realm to the secular space. In time Governments, the military and powerful institutions would use goldwork to signal their authority.

From ecclesiastical robes to the Imperial Mantle worn by a monarch, the rich lustre of gold has long been used to communicate complex meanings. As we have established, in a cathedral setting, it can inspire religious awe whilst in a political setting it is designed to project power and status. On a military body, it communicates power and evokes the vision of ornate armour, whereas, on the body of a 17th-century senior civil servant, it conveys authority and respect.

The projection of such ideas is in part because of the value of the material itself, but that value can be multiplied and augmented in the hands of a skilled embroiderer. When gold is applied to apparel in the form of goldwork embroidery the precious material becomes a reflection of exquisite skill and the multitude of hours worked. The spectacle, the value and the meaning are magnified when gold becomes goldwork embroidery.

In the case of secular uniforms, the goldwork technique has evolved since the days of Opus Anglicanum. Besides passing, other goldwork materials included tightly spun billions, described as Rough, Smooth or Bright Cheque, depending on their lustre.

For uniforms, these tiny coiled wires were cut and applied to the surface a millimetre at a time building up texture and brilliance. They could be placed over raised surfaces creating three-dimensional reliefs that reflected light from all angles. Combined with other common embroidery stitches, embroiderers could create complex leaf and flower motifs.

A court uniform would typically feature elaborate goldwork detailing at the collar, descending down the chest following the buttoned opening, at the hip encircling the waist, on the tails and at the cuffs.

The torso is often finished with a dramatic flourish at the shoulder in the form of a capped sleeve or a dazzling embroidered epaulette. Accompanying trousers would usually have little or no embroidery but would feature some gold detail, usually in the form of woven gold or silver lace on the outer leg or highly polished buttons.

The purpose of this top-heavy embroidery was to emphasise the neoclassical masculine silhouette creating more attention and volume at the upper torso while the lace on the trousers would elongate the lower portion of the wearer’s body. The idealised male proportions reflected in the placement of these embroideries and in the cut and fit of these uniforms were established and codified in the Renaissance and Romantic eras.

Precious metals, artisan skills and the body fuse to communicate something about the situation, the setting and the ritual. In the case of the British Monarch’s bodyguards, or to give them their full and proper title: The Honourable Corps of Gentleman-at-Arms we are looking at a uniform that conveys the endurance of the Royal Family. This uniform mirrors the hyper-masculine silhouette and expresses ideas of power but it also becomes a site for a multitude of different historical eras.

The mediaeval poleaxe is in stark contrast to the feathered plume that might be considered a distant relation of the Galea helmet of the Roman legionaries. Likewise, the decorative aiguillette hanging on the chest of the senior bodyguards evolved from a rope used to tether mediaeval knights to their horses while the pointed tip is a practical tool for clearing muskets ready to reload.

Simultaneously this single decoration recalls links to two distinct points in history.

What does this tell us about the uniform designs we have inherited in the 21st century?

In one respect it is an accidental accumulation of signs and symbols that we now regard as a coherent whole, but likewise, it is a grand deception.

Considering a uniform as Victorian or the Georgian era fails to recognise that decisions were made to combine older styles. In the case of the British Royal Family, who redesigned the Bodyguard uniforms during the aftermath of successive revolutions across Europe, it was a clear attempt to create the illusion of historic continuity.

By projecting a vision of continuity and stability, they could combat the fervent revolutionary sentiment and position the monarchy as central to the British identity.

The Royal families and governments of the world still use uniforms, goldwork, ceremony and ritual to establish the continuity of their power. Seeing ceremonies performed in the 21st century that evoke a connection to the ancient past is intended to provoke a sense of enduring stability and promote trust in the institutions.

The spectacle, the value and the meaning are magnified when gold becomes goldwork embroidery.

The embroidered suit became a ubiquitous garment in the 18th century with richly embroidered court suits and waist jackets worn by men at every formal occasion.

Goldwork embroidery was sometimes supplanted by finely embroidered silk-shaded flowers. These colourful gentlemen could be seen at formal events in Williamsburg Virginia, at the court in Versailles or walking the grounds of Buckingham Palace.

By now we understand that embroidery, as an ancient artisanal craft, is part of a perpetual play for power. Its inaccessibility to most, its revered mystery and its essential value are each significant.

But perhaps, the true measure of its importance is in its connection to the ethereal realm. The cut and the fit, play into neoclassical ideas of proportion and masculinity, but the fine decorations and their long association with Opus Anglicanum, speak to an otherworldliness. To many, gold means God – in fact, in the King James V Bible gold is mentioned 417 times.

But what did it mean when fine goldwork and delicate embroidery began to vanish from the suit?

In Sex & Suits, Anna Hollander writes about the perfect man, dressed in a suit that remakes him as a fusion of Apollo of Greek Myth, Adam of the Christian faith and the quintessential English gentleman. Hollander argues that the earlier use of embroidery and lace, ‘indicated the generic superiority’ of the man and ‘displayed the beauty of the costume’ rather than the man. She suggests that the unadorned material conveyed the neoclassical ideal better.

In a way, her argument demonstrates the romantic and religious attachment to goldwork gradually fell away as the neoclassical ideal fully emerged. This gradual decline of embellished suits occurred after the Enlightenment and as modern production methods called for more streamlined cost-effective clothing. It should be noted that this shift also reflects the slow and gradual decline of religious authority.

The late Victorian era saw the ideal man reject the heavily embroidered court dress. This new man adopted a more modest, unassuming aesthetic and a grand display of opulent wealth was now conveyed through the clothing worn by his wife.

That is not to say the richly embellished suit vanished from formal occasions altogether. Instead, it now became a ceremonial uniform worn on extra special occasions by specific individuals. It was no longer a ubiquitous style of dressing, but instead a symbolic dress of an earlier time.

Now, when we see embroidered suits being worn, it is most likely a formal pageant, a governmental ritual or a secular ceremony.

Besides museums, in Great Britain the state opening of Parliament is an opportunity to see splendid gold embroidered coats in their natural ceremonial setting. When not in use, these embroidered pieces are stored to carefully preserve the embroidery and delicate base fabric of the garments. Meticulously restored time and time again, these beautiful embroidered suits have graduated from the realms of uniform to the heights of historic artefacts. In doing so, they tell us about our history, our ideals, priorities, preoccupations and dreams.